learn it once and for all

At the by end of this article you will

- Understand how Git works at a high level

- Understand the mechanics of git

- Know the most common Git Commands

Git: 3 Tree Setup

As a developer, we are all familiar with Git. Unfortunately besides using a few basic commands, we might not truly understand how it works. That was my case when i first started. I had used cvs as a com sci undergrad, then SVN and SourceSafe after graduation. All of those work quite differently from Git, however initially i used Git as I had used those, mainly with simple commands like git add, commit, and on remote projects with pull, and push.

Traditional version control systems keep everything on the server and clients issued commands to the remote repository for everything like logs, status, versioning, etc. Git, on the other hand, uses a versioning repo on your local machine. That repo can be kept in sync with a remote, but all commit, log, diffs, etc are done locally.

Why this change? Git was developed by Linus Torvalds in 2005. Does that name sound familiar? If not, he’s the guy who initially developed Linux. Git was made to track file versions in a faster, more collaborative, way than the previous client/server systems of the time. For example, while working at AOL, we used SVN, and while I was working on a file(s) I would often tell another developer not to work on it because I was updating it, or when working at another company using SourceSafe, I remember having the ability to lock files while editing so others were unable to modify files I would be working on. One way that Git improves the concurrent programming experience is by keeping the repo local, separate from your working directory, it can pull down changes from the network, updating the local repo, and forces local merges before allowing you to again try to push changes to the remote repo.

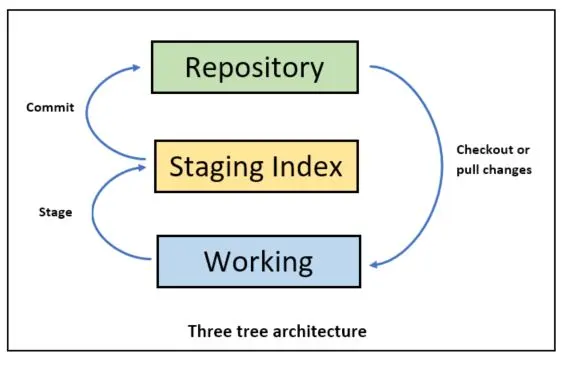

How does this work? It works via a three tree system. Basically, besides your local working files, there’s also the Git project repo which keeps track of everything related version control, and there’s a final tree which consists of files to be committed to the git repo, staging.

Why this 3 tree system on your local machine? First, it’s much faster than making network requests for each action, second it works offline, and last it’s more robust to have multiple copies of the repo on numerous machines, rather than a sole master copy on a remote server. You might think that each workstation is duplicating information locally, and you are right, all files and versions are on each workstation, however git stores the repo in an efficient/compressed manner and the benefits outweigh the extra cost of storing a local repo storage.

Why this 3 tree system on your local machine? First, it’s much faster than making network requests for each action, second it works offline, and last it’s more robust to have multiple copies of the repo on numerous machines, rather than a sole master copy on a remote server. You might think that each workstation is duplicating information locally, and you are right, all files and versions are on each workstation, however git stores the repo in an efficient/compressed manner and the benefits outweigh the extra cost of storing a local repo storage.

One key advantage of this setup is the easy ability to switch your working directly to any commit in the repo via the checkout command followed by the version you’d like to switch to. Without a version argument like a commit hash or tag, you’ll get the head or latest version for that branch.

Regarding staging, you might be wondering why it’s used, rather than simply committing working directory changes directly to the repository. Often this is the case, and I’ll commit using “git commit -am” which will add working directly change to staging, and commit them. However, there are often situations where you could have many many changes to your working directly or even an individual file and would prefer to commit the changes in separate stages. The staging directory allows us to cherry pick working directly files or even parts for changes to a file to be bundled into the staging directly, and ready to be committed to the repository.

Where do these tree’s live? As mentioned, they are all local. Your working directory is the folder that you either called “git init” or “git clone” in. In that directory you will find the .git directory, which is your local git repository. In that directory you’ll also find a file called index which functions to track changes you’ve added to staging.

Git Mechanics

Now that you understand the basics of the three Git trees, it’s time to learn how to manipulate them and how Git tracks files and versions behind the scene.

Git primarily stores three types of objects: commits, trees, and blobs. Blobs are common files, while a tree is meant to capture a snapshot or version of your project, a commit links a parent commit to the newly created one along with: the staged tree, author, and committer information.

The git repository uses these commits to track a history of changes. There are important pointers or references to them, namely branches and the HEAD. The default main branch used to be called Master, though that’s recently been changed to Main, and the HEAD typically points to the top or last commit of the current branch.

Good Habits When Working on Teams

When branching, decide on a naming scheme which reflects what the code will be related to, for example: feature-addTaskReminders or bugfix-128allowCleanReload

Always work on branches rather than Main/Master. Also, over time, delete old branches which have already been merged. The merge commit should have enough information to know what the branch did so the branch name is no longer necessary.

Commit messages

You message should fit into this phrase, “This commit will…[commit-message].” It should start with an action, be present tense.

Have a standard team git environment

Similar to coding standards, you should have agreed upon setup for git_ignore files. One is system level git ignore files, and local project based .git_ignore files. A good resource to generate them is: https://www.toptal.com/developers/gitignore

Clarification Commands

When Git was created, there were a few basic commands were generic. As features were added, the same commands were called, but with new parameters, often doing more than originally intended. Often the commands themselves made Git much more difficult to understand. In 2019 with version 2.23, Git added new commands. To maintain backwards compatibility, the original ones still work, but the newer ones are more readable and are limited to specific actions.

git show == git diff prevComment lastCommit

I typically use show to check what changes were made by the last commit, and diff for changes between staging and my working directory or between to arbitrary commits.

git switch [branchname] == git checkout [branchname]

Both of these work to switch a branch, and can create a new one by passing -c or -b respectively.

git restore [filename] == git checkout [filename]

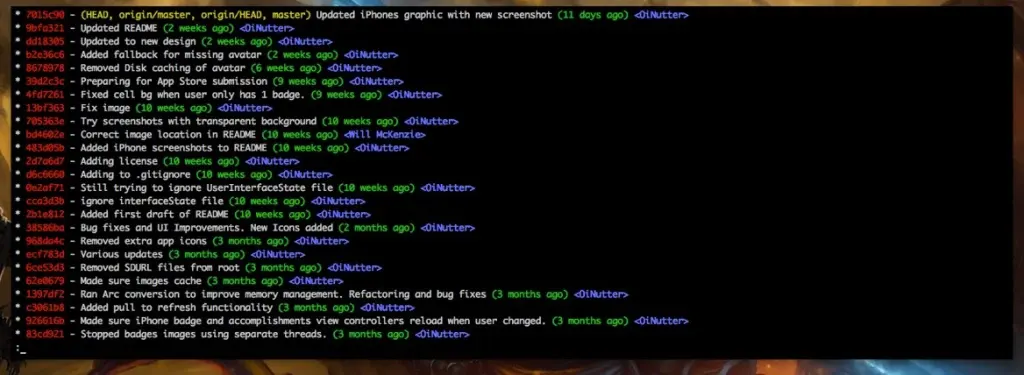

Bonus Git Logging

One of the most common commands you’ll use, besides git status, is git log. Here’s an alias to output a more readable report:

git config --global alias.lg "log --color --graph --pretty=format:'%Cred%h%Creset -%C(yellow)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr) %C(bold blue)<%an>%Creset' --abbrev-commit"Git Commands Cheatsheet

git diff //shows delta between wDir and Staged

git diff —staged //delta between Staged and HEAD

git diff [HEAD3] //delta betweeen working directory and 3 commits ago1] //shows diff for last committ

git diff master..origin^ //compare 2 branches

git branch —merged //looks at branches to see if some are comletely contained in others

git log —oneline //summary of log

git status // checks staged index and working dir changes from HEAD

git clean [-n //test, -f //force run] //remove files from working directory

git ls-tree [HEAD] //gives file listing of what’s in HEAD

git show —oneline [HEAD

git stash save “some message” // stashes tracked files, use -u to include untracked files

git stash list //get a list of stashed files

git stash show -p stash@{0} //to see the diff stat

git stash pop [stash@{0}] //remove last and merge into wDir

git stash apply //only merge into wDir

git stash drop [stash@{0}] //delete from stash

git stash clear //removes all of stashes

changing 3 trees: HEAD, Index, wDir

//commit level changes, ie HEAD^, HEAD~2, Commit Hash, etc

git reset —soft [HEAD^] //changes only HEAD reference

git reset [HEAD^] //changes HEAD & wDir

git reset —hard [HEAD^] //changes all trees, blows away wDir, after might need to update branch

git checkout [HEAD^] //changes all trees, will attempt to merge changes. if conflict, will not allow.

git revert [HEAD^] //will completely undo a commmit by replaying the opposite of the changes and commiting

//file level changes, ie index.html

reset [HEAD^] [fileName] // updates only Index

checkout [HEAD^] [fileName] // updates index and wDir, forcefully updates

git remote add // add a remote

git branch -a //view all branches

git branch -r //view remote branches

git push origin [some local branch] //create a branch on remote/origin server

git push origin —delete [some local branch] //delete a branch on a remote/origin server

git fetch -p //prune remote local branches that do not exist on remote

got checkout -b [some new branch] [where are branching from]

git help [some term or command]

git commit —allow-empty -m ‘push to execute post-receive’ // push empty commit

References

http://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Internals-Git-Objects

https://dev.to/milu_franz/git-explained-proper-team-etiquette-1od

https://redfin.engineering/two-commits-that-wrecked-the-user-experience-of-git-f0075b77eab1